A short text on how objects of language can shape public debate and therefore public opinion.

On January 9 2007, Steve Jobs — former CEO of Apple — presented a keynote at the Macworld event. In this presentation he revealed a widescreen iPod with touch controls, a revolutionary mobile phone and a breakthrough internet communicator. Not three devices, but one. It was the iPhone, which would reset the whole mobile phone market from that point on. Not only that, it changed the way we interact and move through public space fundamentally, staring down at our own devices. This has both social and physical effects on smartphone users, a ‘Text Neck’ is reported to be a growing problem. So it is safe to conclude that objects — at least in certain cases — can intervene with our behaviour and possibly also our thinking.

Nicole Boivin, an archaeologist from Oxford University, researches the agency of materials and objects. “For example, among many agricultural groups, renewal of dwellings made from impermanent materials — mud and thatch — serve to renew kin ties of particular kinds and underscore gender roles and duties.

Building materials in dwellings have impact on our social behaviour.

What happens when, without other changes in technology and subsistence, fragile building materials are replaced by concrete blocks and tin roofs? Certainly the structure of society will be weakened and perhaps transformed through the agency of building materials.”1

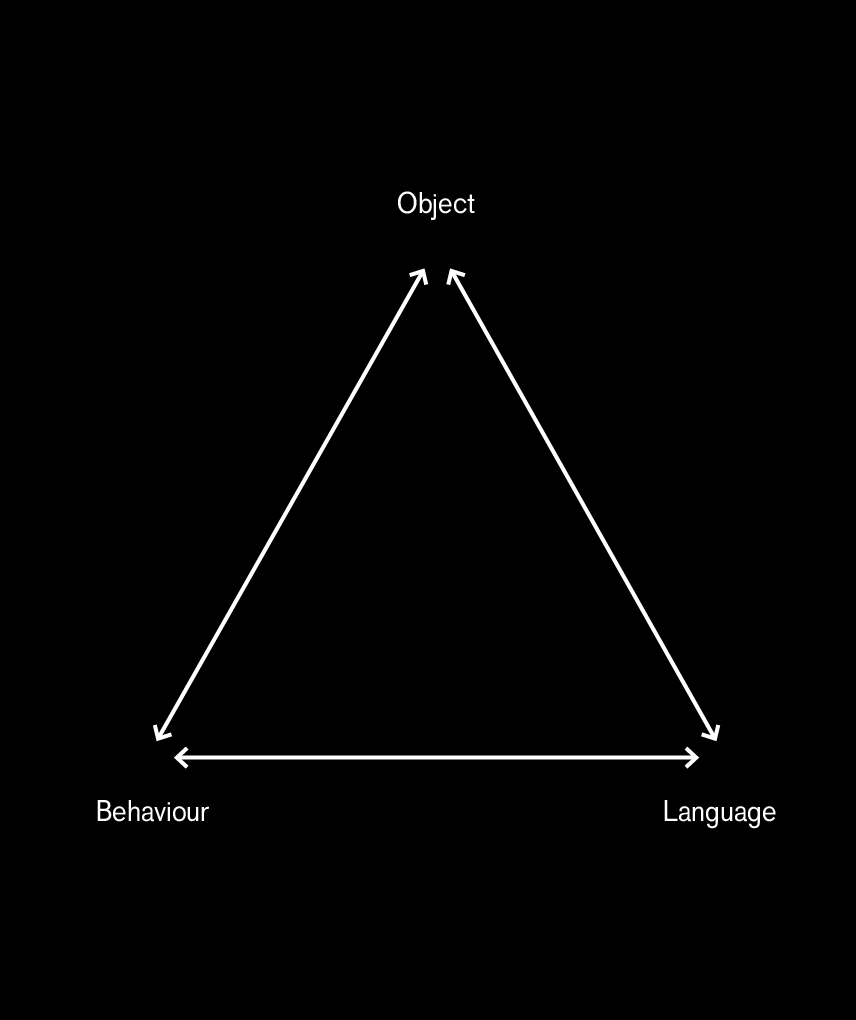

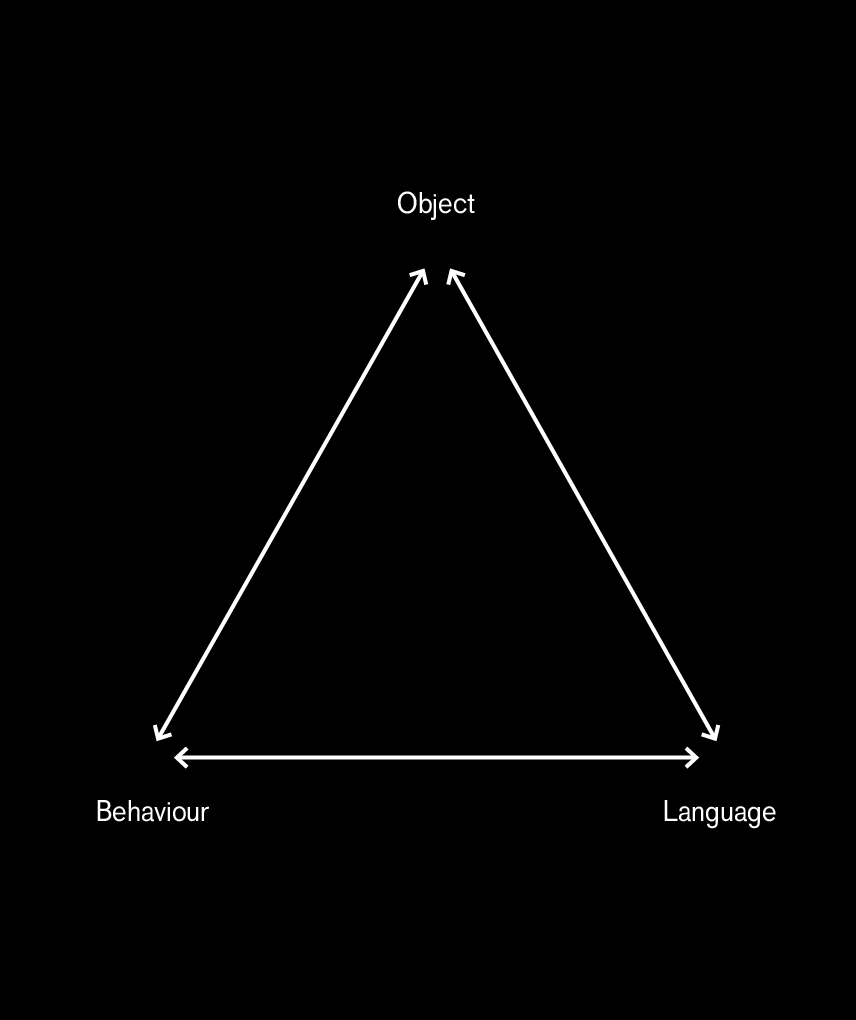

Our perceptions of, and actions within, our surroundings are changed under the power of the implementation of objects. While this is true for the physical object, it is also to some extent applicable to language, the tool of politics. “Man is suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun.”2

In this essay I would like to research how Wilders designs his political rhetorics, and why he is — in this sense — a better designer than other politicians.

For a better understanding of how language influences our behaviour, I will refer to and quote the work of Lera Boroditsky. She is an associate professor of Cognitive Science at UCSD and Editor in Chief of Frontiers in Cultural Psychology. She poses that the idea that language could shape our thinking was for a long time considered “at best untestable and more often simply wrong”. Her research at Stanford University and MIT opened up new views on the subject, concluding that language indeed has the power to “profoundly affect how we see the world”.3

The Kuuk Thaayorre

Can we still navigate?

Boroditsky has for example examined the spatial influences of language on Aboriginal groups in Australia.

“The Kuuk Thaayorre, like many other Aboriginal groups, use cardinal-direction terms — north, south, east, and west — to define space. This is done at all scales, which means you have to say things like ‘There’s an ant on your southeast leg’ or ‘Move the cup to the north northwest a little bit.’ One obvious consequence of speaking such a language is that you have to stay oriented at all times, or else you cannot speak properly. The normal greeting in Kuuk Thaayorre is ‘Where are you going?’ and the answer should be something like ‘Southsoutheast, in the middle distance.’ If you don’t know which way you’re facing, you can’t even get past ‘Hello’. The result is a profound difference in navigational ability and spatial knowledge between speakers [...] Simply put, speakers of languages like Kuuk Thaayorre are much better than English speakers at staying oriented and keeping track of where they are, even in unfamiliar landscapes or inside unfamiliar buildings. What enables them — in fact, forces them — to do this is their language. Having their attention trained in this way equips them to perform navigational feats once thought beyond human capabilities.”4

‘Keys’ according to the Germans

“Does treating chairs as masculine and beds as feminine in the grammar make Russian speakers think of chairs as being more like men and beds as more like women in some way? It turns out that it does. In one study, we asked German and Spanish speakers to describe objects having opposite gender assignment in those two languages. The descriptions they gave differed in a way predicted by grammatical gender. For example, when asked to describe a ‘key’ — a word that is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish — the German speakers were more likely to use words like ‘hard,’ ‘heavy,’ ‘jagged,’ ‘metal,’ ‘serrated,’ and ‘useful,’ whereas Spanish speakers were more likely to say ‘golden,’ ‘intricate,’ ‘little,’ ‘lovely,’ ‘shiny,’ and ‘tiny.’ To describe a ‘bridge,’ which is feminine in German and masculine in Spanish, the German speakers said ‘beautiful,’ ‘elegant,’ ‘fragile,’ ‘peaceful,’ ‘pretty,’ and ‘slender,’ and the Spanish speakers said ‘big,’ ‘dangerous,’ ‘long,’ ‘strong,’ ‘sturdy,’ and ‘towering.’ This was true even though all testing was done in English, a language without grammatical gender. [...] Apparently even small flukes of grammar, like the seemingly arbitrary assignment of gender to a noun, can have an effect on people’s ideas of concrete objects in the world.”5

‘Keys’ according to the Spanish

Another research conducted by a team of MIT, led by Edward Gibson, depicts an Indian tribe — the Pirahã — that does not use numbers in their lingual system as western languages do. The team found that the Pirahã only use three types of words to describe quantity, similar to how we would use one, two and many. They came to this conclusion by starting with one object to be counted, and adding one object at a time, up until 10. But when they worked the other way around, counting down, they found that the Pirahã used the term previously understood as two; now was used to signify six or five objects. And they used the term previously signifying one for four to one object(s). This led to Gibsons conclusion that “they’re signifying relative quantities”, and never absolute quantities. Meaning that the Pirahã are comparing amounts, rather than counting them.

Language does not only have similarities with the object, regarding influence in the way we act, it is also often referred to as being an actual object or device. This opens up new perspectives on its use, its power to create new realities and ability to be designed and shaped. Derek Bickerton for example states that “language is unique to humans, but it isn’t the only thing that sets us apart from other species — our cognitive powers are qualitatively different. So could there be two separate discontinuities between humans and the rest of nature? No, says Bickerton; he shows how the mere possession of symbolic units — words — automatically opened a new and different cognitive universe, one that yielded novel innovations ranging from barbed arrowheads to the Apollo spacecraft."6

Apollo 17 in orbit, a product of our imagination.

Foucault introduces the term dispositif or apparatus referring to relational systems of institutions, discourses, measures, statements, architectural forms, morals et cetera. The said and the unsaid. The apparatus is an object that has the power to impose. Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben builds on Foucaults definition of the apparatus. “Further expanding the already large class of Foucauldian apparatuses, I shall call an apparatus literally anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control, or secure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings. Not only, therefore, prisons, madhouses, the panopticon, schools, confession, factories, disciplines, judicial measures, and so forth (whose connection with power is in a certain sense evident), but also the pen, writing, literature, philosophy, agriculture, cigarettes, navigation, computers, cellular telephones and — why not — language itself, which is perhaps the most ancient of apparatuses — one in which thousands and thousands of years ago a primate inadvertently let himself be captured, probably without realizing the consequences that he was about to face."7

Dealing with a new reality

Nicole Boivin refers to a theory called niche construction in her paper Material Cultures, Material Minds. This is a process whereby humans, and other organisms, construct and modify their own and other niches. The change of one niche puts pressure on another, therefore altering the evolutionary dynamic. Boivin writes that “whether for earthworms, beaver, or humans, is the proposition that organisms construct ecological niches for themselves as part of their being-in-the-world, as a way of counteracting and buffering the vagaries of a hostile environment. This act of construction, which for humans incorporates their symbolic faculties, themselves an evolutionary product, covers the full range of material, organizational and phenotypic assets of our species.” And as Derek Bickerton wrote: “Human culture is just the human niche”. These niches respond to new objects of reality, wherein lingual objects are as ‘real’ as physical objects, this is what Bickerton referred to as “a new and different cognitive universe."8

Cultural ecosystem

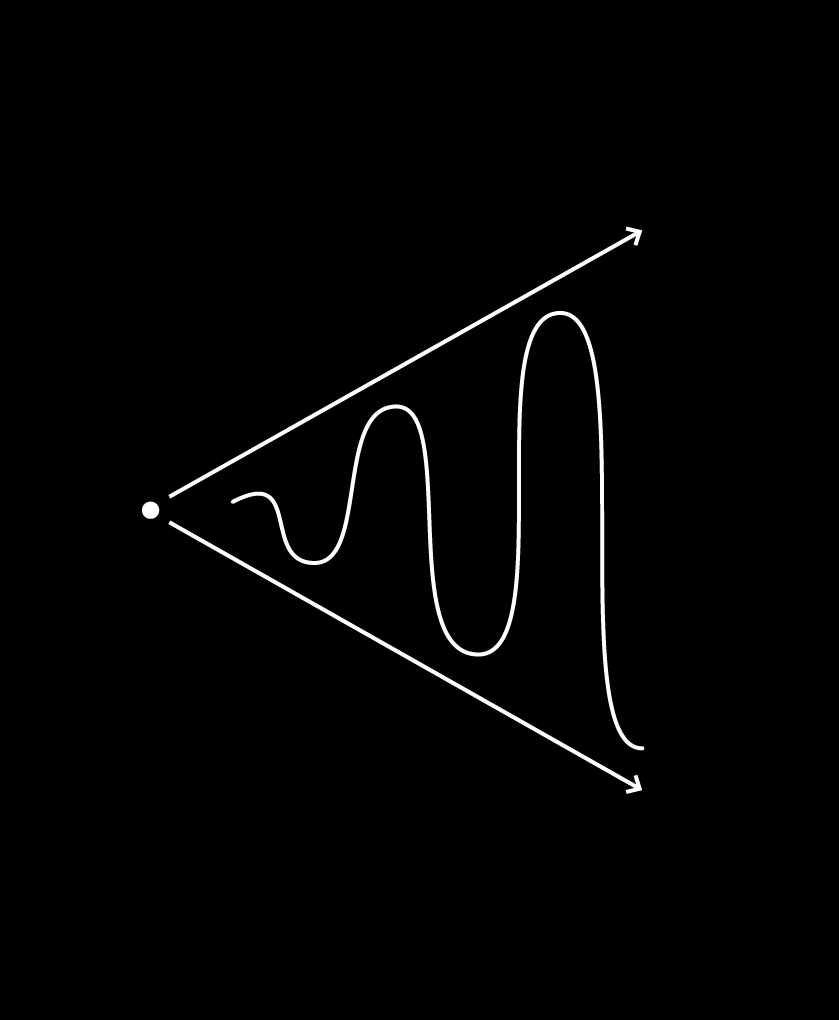

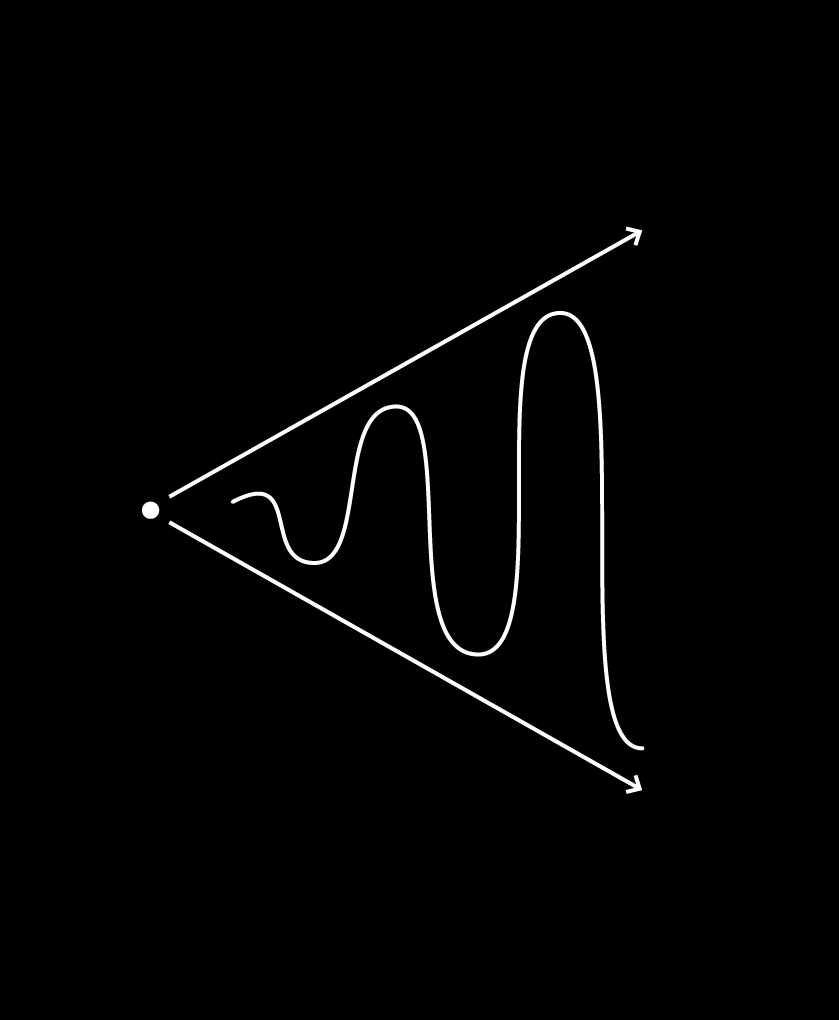

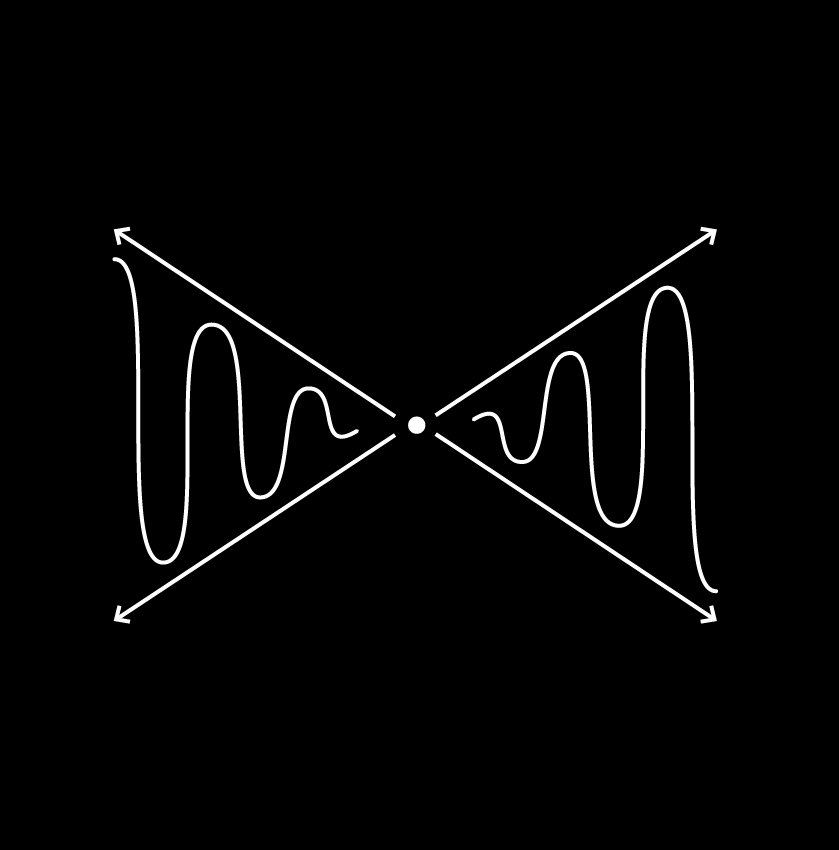

While language has the ability to create new objects of reality, which can be referred to as priming, it has at the same time the possibility of altering existing realities, this is done by framing. The theory of priming is grounded in cognitive psychology and is focused on the associative network model of the human memory. An idea is conceived as a node, and is interconnected with other nodes (ideas).

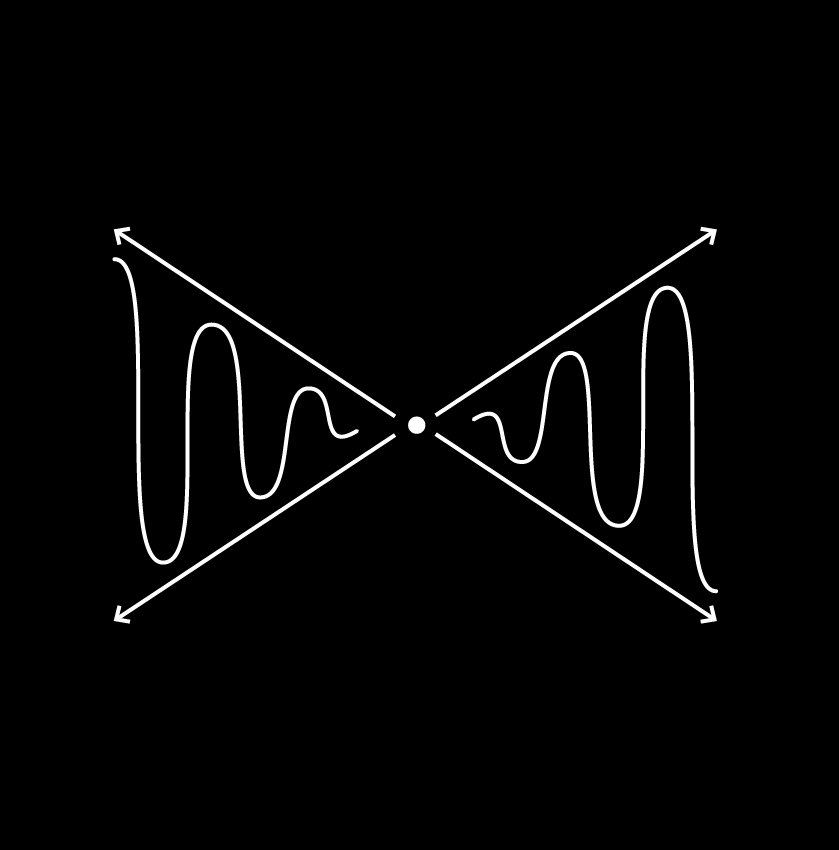

Semantic Networks. Priming and spreading activation of thought and concepts through the networks.

In The Psychology of Stereotyping David J. Schneider, an American psychologist, gives us two examples of the priming theory.

“The O.J. Simpson trial provided one of the largest splits between races on attitudes in modern history. A CBS poll taken just after the verdict showed that 78% of blacks thought he was innocent and 75% of whites believed he was guilty. Such huge differences cannot easily be explained in terms of the relative stupidity, ignorance, or bias of one race or the other. One reason for the profound disagreements between black and white Americans on the guilt of Simpson was the way the two groups framed the issues and images. The mainstream media clearly framed the issues in terms of black stereotypes (Simpson as illiterate, stupid, violent, and sex-crazed) and emphasized evidence that pointed to his guilt. Not surprisingly, blacks tended to be put off by these presentations and to look for other realities. [...] A dramatic example of such priming occurred during the 1988 Presidential race between the elder George Bush and Michael Dukakis. In early October, the Bush campaign began emphasizing what came to be known as the ‘Willie Horton ad.’ Horton, a black man, was a convicted murderer who while on a Massachusetts furlough program had terrorized a white couple in Maryland. Dukakis, then governor of Massachusetts, defended the furlough program. Because pictures of Willie Horton featured prominently in the televised ad made it clear that he was black, it is probable that these ads primed anti-black attitudes. In any event, after the beginning of the ads, racial resentment became a much more powerful predictor of voting for Bush."9

Framing however works somewhat differently. Frames or a framing device can be seen as a certain perspective or framework, used to perceive a certain subject. This frame typically leaves out parts of the bigger picture in order to convey a specific point of view, making the subject even more vulnerable for interpretation and individual perception. Professor D. Pinto in his book Beeldvorming en integratie writes about frames as being descriptions of reality, used as a guidance in the interpretation of it. It is human to divide people within your environment up into groups by guides as sex, religion, etnicity, heritage, language, occupation and place of residence. This could lead to having prejudices about these people. The power of frames is that they strengthen themselves, a frame does not neccesarily have to be true, but by being introduced and discussed, it will become a reality or object of reality. Responding negatively to — or disagreeing with the frame used only helps create the object, because it does not deny the existence of the frame, it rather confirms it.

Framing resonance

A way to perceive the influence of language is to register neologisms, new terms that have added to the enormous array of existing ones. Let us take a look at the Word of the Year, between 2005 and 2015. An election of words that are deemed to be the most influential, significant or contemporary that year. The list presented is made up by words that got elected by Dutch institutions and organisations (Genootschap onze taal & van Dale), and therefore are mostly Dutch terms.

Neologisms are a way to keep track of the impact of language.

2014

Rampvlucht

Dagobert Duck taks

2013

Participatiesamenleving

Selfie

2012

Plofkip

Project X feest

2011

Weigerambtenaar

Tuigdorp

2010

Gedoogsteun

Gedoogregering

2009

Twitteren

Ontvrienden

2008

Swaffelen

2007

Bokitoproof

2006

VOC mentaliteit

2005

Generatiepact

A large part of the elected words or terms have a political background, origin or even motif, suggesting a close relation between politics and language. Are these neologisms the result of politics being in the public sphere, responding to a new reality? Or are they deliberately put to use in order to create new realities?

Geert Wilders (PVV)

Staying focussed on the Netherlands, it could be interesting to consider the lingual contributions of Geert Wilders, of the populist political party PVV. Although despised by many, Wilders also is very popular under large parts of the electorate. He, as no one else, shows how powerful framing can be within public debate. Journalist J. Kuitenbrouwer, in his book De woorden van Wilders en hoe ze werken, states the following: “If Islamisation exists or not, Wilders introduces it as a topic [...] and forces others to comment on it. Therefore it exists.” Professor Tjitske Akkerman, in her article Populism and Democracy: Challenge or Pathology? attributes the electoral succes of Wilders to the combination of preferences of society and marketing techniques with strong leadership and the taking of simple and clear positions. And the neologisms of Wilders help him achieve this, they are priming and framing political debate and therefore influencing the minds of the electorate. He is deliberately creating some sort of vernacular or bridge language between the politics and the people, handing the people tools, framing devices or reasoning devices in order to engage the political debate in their own way. And whether we despise or vote for Wilders, we all have to deal with the new realities he is shaping.

How to escape the frame?

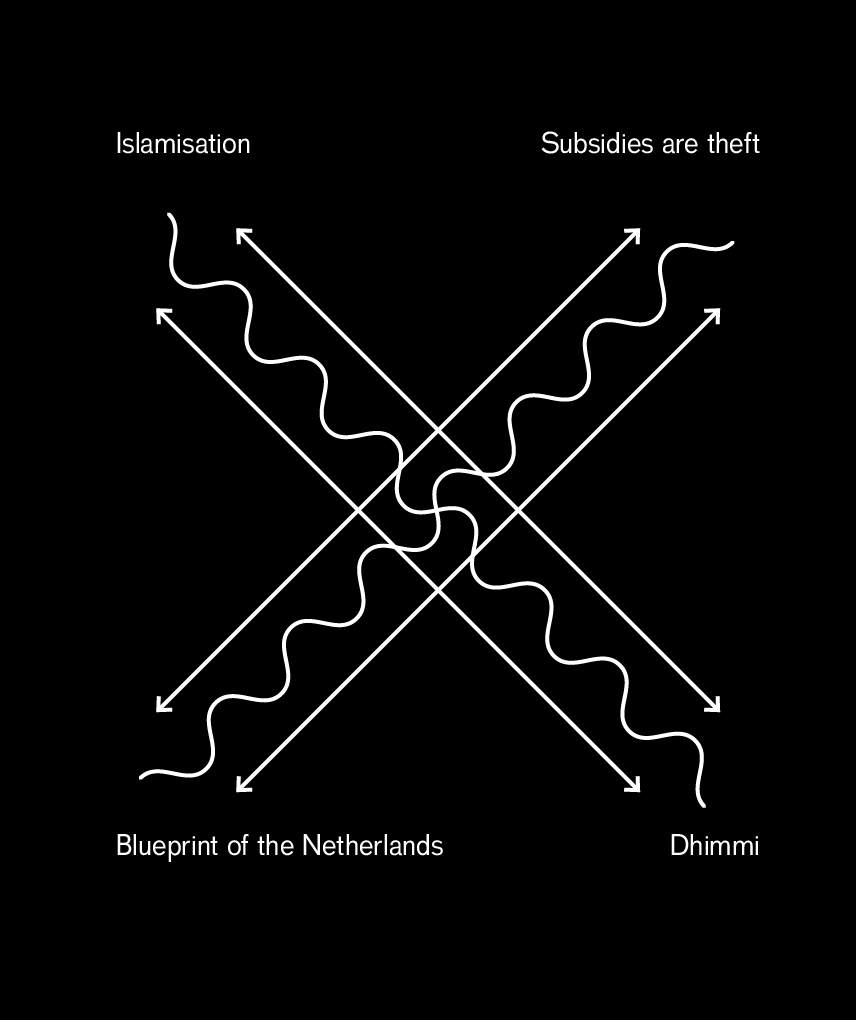

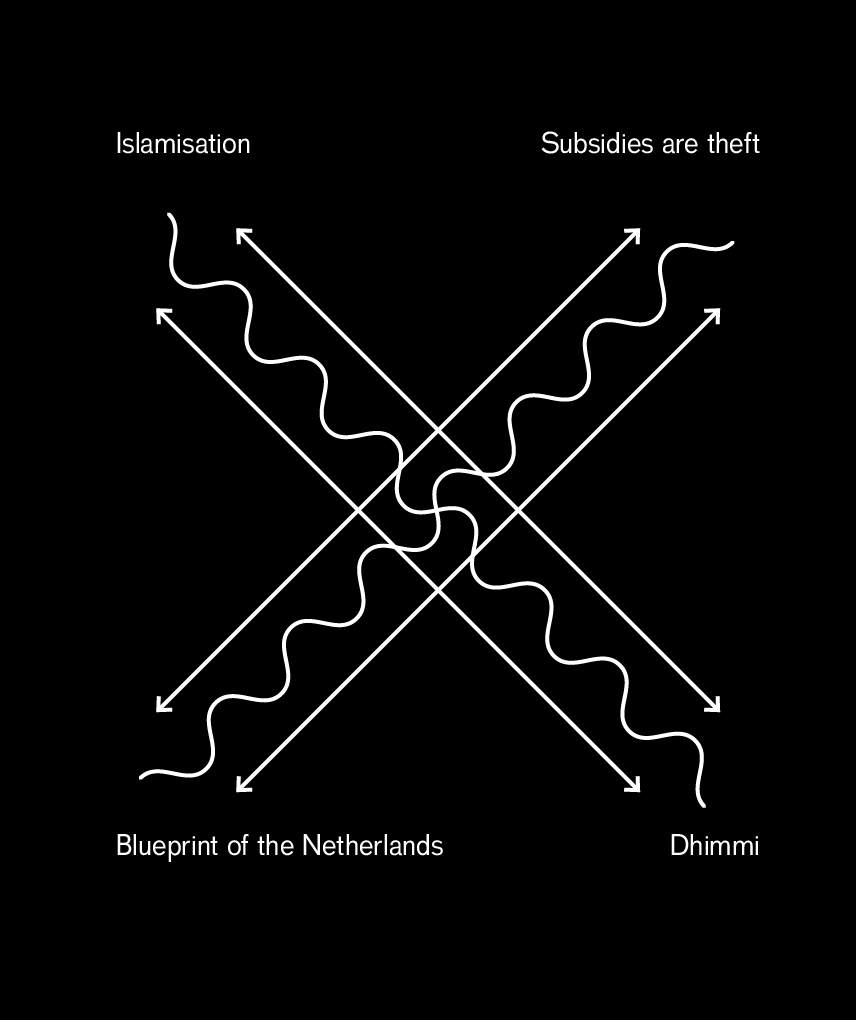

Kuitenbrouwer researched the use of frames by Wilders, and ended up with four main frames he is referring to in debates or public talks, the Islamisation, Subsidies are Theft, Blueprint of the Netherlands and the Dhimmi frame. I will not go into them separately, but having only four frames displays the simplicity and clarity he is using to display the urgence of todays politics. Looking at some of the words that Wilders introduced, it is easy to see how they might have sparked political debate within a certain frame.

Next to these neologisms or new combinations, Wilders is also known for his frequent use of tropes, superlatives (“Worst government ever”) and hyperboles (“tsunami” or “disaster”) as described in the classic rhetorics of Aristotle, the art of persuasion. So next to priming, framing, fallacies are also part of Wilders’ design tools.

Neologisms of Geert Wilders10

AI Gore-papegaai

Gedachtepolitie

Haatbaard

Haatimam

Heimweeschotel

Henk en Ingrid

Hollandistan

Kopvoddentaks

Linkse hobby’s

Multicul

Overlegpaleizen

Rabat aan de Rijn

Wilders’ frames according to Kuitenbrouwer

The question rises, if Wilders is so succesful in creating or designing these new objects of reality — with questionable motives — is it not possible to repurpose these techniques in a more constructive way, if language can be perceived as being an object, is it also possible to use design-methodologies in order to construct and shape it? At least it could be useful to analyse and visualise the workings of Wilders’ designs in order to better understand and defuse them. Only then are we able to level the playing field again.

Geert Wilders does not only design his rhetorics, he also dyes his hair in a blonde color. It is assumed that he wants to hide his Indonesian roots.

A short text on how objects of language can shape public debate and therefore public opinion.

On January 9 2007, Steve Jobs — former CEO of Apple — presented a keynote at the Macworld event. In this presentation he revealed a widescreen iPod with touch controls, a revolutionary mobile phone and a breakthrough internet communicator. Not three devices, but one. It was the iPhone, which would reset the whole mobile phone market from that point on. Not only that, it changed the way we interact and move through public space fundamentally, staring down at our own devices. This has both social and physical effects on smartphone users, a ‘Text Neck’ is reported to be a growing problem. So it is safe to conclude that objects — at least in certain cases — can intervene with our behaviour and possibly also our thinking.

Nicole Boivin, an archaeologist from Oxford University, researches the agency of materials and objects. “For example, among many agricultural groups, renewal of dwellings made from impermanent materials — mud and thatch — serve to renew kin ties of particular kinds and underscore gender roles and duties.

Building materials in dwellings have impact on our social behaviour.

What happens when, without other changes in technology and subsistence, fragile building materials are replaced by concrete blocks and tin roofs? Certainly the structure of society will be weakened and perhaps transformed through the agency of building materials.”11

Our perceptions of, and actions within, our surroundings are changed under the power of the implementation of objects. While this is true for the physical object, it is also to some extent applicable to language, the tool of politics. “Man is suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun.”12

In this essay I would like to research how Wilders designs his political rhetorics, and why he is — in this sense — a better designer than other politicians.

For a better understanding of how language influences our behaviour, I will refer to and quote the work of Lera Boroditsky. She is an associate professor of Cognitive Science at UCSD and Editor in Chief of Frontiers in Cultural Psychology. She poses that the idea that language could shape our thinking was for a long time considered “at best untestable and more often simply wrong”. Her research at Stanford University and MIT opened up new views on the subject, concluding that language indeed has the power to “profoundly affect how we see the world”.13

The Kuuk Thaayorre

Can we still navigate?

Boroditsky has for example examined the spatial influences of language on Aboriginal groups in Australia.

“The Kuuk Thaayorre, like many other Aboriginal groups, use cardinal-direction terms — north, south, east, and west — to define space. This is done at all scales, which means you have to say things like ‘There’s an ant on your southeast leg’ or ‘Move the cup to the north northwest a little bit.’ One obvious consequence of speaking such a language is that you have to stay oriented at all times, or else you cannot speak properly. The normal greeting in Kuuk Thaayorre is ‘Where are you going?’ and the answer should be something like ‘Southsoutheast, in the middle distance.’ If you don’t know which way you’re facing, you can’t even get past ‘Hello’. The result is a profound difference in navigational ability and spatial knowledge between speakers [...] Simply put, speakers of languages like Kuuk Thaayorre are much better than English speakers at staying oriented and keeping track of where they are, even in unfamiliar landscapes or inside unfamiliar buildings. What enables them — in fact, forces them — to do this is their language. Having their attention trained in this way equips them to perform navigational feats once thought beyond human capabilities.”14

‘Keys’ according to the Germans

“Does treating chairs as masculine and beds as feminine in the grammar make Russian speakers think of chairs as being more like men and beds as more like women in some way? It turns out that it does. In one study, we asked German and Spanish speakers to describe objects having opposite gender assignment in those two languages. The descriptions they gave differed in a way predicted by grammatical gender. For example, when asked to describe a ‘key’ — a word that is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish — the German speakers were more likely to use words like ‘hard,’ ‘heavy,’ ‘jagged,’ ‘metal,’ ‘serrated,’ and ‘useful,’ whereas Spanish speakers were more likely to say ‘golden,’ ‘intricate,’ ‘little,’ ‘lovely,’ ‘shiny,’ and ‘tiny.’ To describe a ‘bridge,’ which is feminine in German and masculine in Spanish, the German speakers said ‘beautiful,’ ‘elegant,’ ‘fragile,’ ‘peaceful,’ ‘pretty,’ and ‘slender,’ and the Spanish speakers said ‘big,’ ‘dangerous,’ ‘long,’ ‘strong,’ ‘sturdy,’ and ‘towering.’ This was true even though all testing was done in English, a language without grammatical gender. [...] Apparently even small flukes of grammar, like the seemingly arbitrary assignment of gender to a noun, can have an effect on people’s ideas of concrete objects in the world.”15

‘Keys’ according to the Spanish

Another research conducted by a team of MIT, led by Edward Gibson, depicts an Indian tribe — the Pirahã — that does not use numbers in their lingual system as western languages do. The team found that the Pirahã only use three types of words to describe quantity, similar to how we would use one, two and many. They came to this conclusion by starting with one object to be counted, and adding one object at a time, up until 10. But when they worked the other way around, counting down, they found that the Pirahã used the term previously understood as two; now was used to signify six or five objects. And they used the term previously signifying one for four to one object(s). This led to Gibsons conclusion that “they’re signifying relative quantities”, and never absolute quantities. Meaning that the Pirahã are comparing amounts, rather than counting them.

Language does not only have similarities with the object, regarding influence in the way we act, it is also often referred to as being an actual object or device. This opens up new perspectives on its use, its power to create new realities and ability to be designed and shaped. Derek Bickerton for example states that “language is unique to humans, but it isn’t the only thing that sets us apart from other species — our cognitive powers are qualitatively different. So could there be two separate discontinuities between humans and the rest of nature? No, says Bickerton; he shows how the mere possession of symbolic units — words — automatically opened a new and different cognitive universe, one that yielded novel innovations ranging from barbed arrowheads to the Apollo spacecraft."16

Apollo 17 in orbit, a product of our imagination.

Foucault introduces the term dispositif or apparatus referring to relational systems of institutions, discourses, measures, statements, architectural forms, morals et cetera. The said and the unsaid. The apparatus is an object that has the power to impose. Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben builds on Foucaults definition of the apparatus. “Further expanding the already large class of Foucauldian apparatuses, I shall call an apparatus literally anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control, or secure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings. Not only, therefore, prisons, madhouses, the panopticon, schools, confession, factories, disciplines, judicial measures, and so forth (whose connection with power is in a certain sense evident), but also the pen, writing, literature, philosophy, agriculture, cigarettes, navigation, computers, cellular telephones and — why not — language itself, which is perhaps the most ancient of apparatuses — one in which thousands and thousands of years ago a primate inadvertently let himself be captured, probably without realizing the consequences that he was about to face."17

Dealing with a new reality

Nicole Boivin refers to a theory called niche construction in her paper Material Cultures, Material Minds. This is a process whereby humans, and other organisms, construct and modify their own and other niches. The change of one niche puts pressure on another, therefore altering the evolutionary dynamic. Boivin writes that “whether for earthworms, beaver, or humans, is the proposition that organisms construct ecological niches for themselves as part of their being-in-the-world, as a way of counteracting and buffering the vagaries of a hostile environment. This act of construction, which for humans incorporates their symbolic faculties, themselves an evolutionary product, covers the full range of material, organizational and phenotypic assets of our species.” And as Derek Bickerton wrote: “Human culture is just the human niche”. These niches respond to new objects of reality, wherein lingual objects are as ‘real’ as physical objects, this is what Bickerton referred to as “a new and different cognitive universe."18

Cultural ecosystem

While language has the ability to create new objects of reality, which can be referred to as priming, it has at the same time the possibility of altering existing realities, this is done by framing. The theory of priming is grounded in cognitive psychology and is focused on the associative network model of the human memory. An idea is conceived as a node, and is interconnected with other nodes (ideas).

Semantic Networks. Priming and spreading activation of thought and concepts through the networks.

In The Psychology of Stereotyping David J. Schneider, an American psychologist, gives us two examples of the priming theory.

“The O.J. Simpson trial provided one of the largest splits between races on attitudes in modern history. A CBS poll taken just after the verdict showed that 78% of blacks thought he was innocent and 75% of whites believed he was guilty. Such huge differences cannot easily be explained in terms of the relative stupidity, ignorance, or bias of one race or the other. One reason for the profound disagreements between black and white Americans on the guilt of Simpson was the way the two groups framed the issues and images. The mainstream media clearly framed the issues in terms of black stereotypes (Simpson as illiterate, stupid, violent, and sex-crazed) and emphasized evidence that pointed to his guilt. Not surprisingly, blacks tended to be put off by these presentations and to look for other realities. [...] A dramatic example of such priming occurred during the 1988 Presidential race between the elder George Bush and Michael Dukakis. In early October, the Bush campaign began emphasizing what came to be known as the ‘Willie Horton ad.’ Horton, a black man, was a convicted murderer who while on a Massachusetts furlough program had terrorized a white couple in Maryland. Dukakis, then governor of Massachusetts, defended the furlough program. Because pictures of Willie Horton featured prominently in the televised ad made it clear that he was black, it is probable that these ads primed anti-black attitudes. In any event, after the beginning of the ads, racial resentment became a much more powerful predictor of voting for Bush."19

Framing however works somewhat differently. Frames or a framing device can be seen as a certain perspective or framework, used to perceive a certain subject. This frame typically leaves out parts of the bigger picture in order to convey a specific point of view, making the subject even more vulnerable for interpretation and individual perception. Professor D. Pinto in his book Beeldvorming en integratie writes about frames as being descriptions of reality, used as a guidance in the interpretation of it. It is human to divide people within your environment up into groups by guides as sex, religion, etnicity, heritage, language, occupation and place of residence. This could lead to having prejudices about these people. The power of frames is that they strengthen themselves, a frame does not neccesarily have to be true, but by being introduced and discussed, it will become a reality or object of reality. Responding negatively to — or disagreeing with the frame used only helps create the object, because it does not deny the existence of the frame, it rather confirms it.

Framing resonance

A way to perceive the influence of language is to register neologisms, new terms that have added to the enormous array of existing ones. Let us take a look at the Word of the Year, between 2005 and 2015. An election of words that are deemed to be the most influential, significant or contemporary that year. The list presented is made up by words that got elected by Dutch institutions and organisations (Genootschap onze taal & van Dale), and therefore are mostly Dutch terms.

Neologisms are a way to keep track of the impact of language.

2014

Rampvlucht

Dagobert Duck taks

2013

Participatiesamenleving

Selfie

2012

Plofkip

Project X feest

2011

Weigerambtenaar

Tuigdorp

2010

Gedoogsteun

Gedoogregering

2009

Twitteren

Ontvrienden

2008

Swaffelen

2007

Bokitoproof

2006

VOC mentaliteit

2005

Generatiepact

A large part of the elected words or terms have a political background, origin or even motif, suggesting a close relation between politics and language. Are these neologisms the result of politics being in the public sphere, responding to a new reality? Or are they deliberately put to use in order to create new realities?

Geert Wilders (PVV)

Staying focussed on the Netherlands, it could be interesting to consider the lingual contributions of Geert Wilders, of the populist political party PVV. Although despised by many, Wilders also is very popular under large parts of the electorate. He, as no one else, shows how powerful framing can be within public debate. Journalist J. Kuitenbrouwer, in his book De woorden van Wilders en hoe ze werken, states the following: “If Islamisation exists or not, Wilders introduces it as a topic [...] and forces others to comment on it. Therefore it exists.” Professor Tjitske Akkerman, in her article Populism and Democracy: Challenge or Pathology? attributes the electoral succes of Wilders to the combination of preferences of society and marketing techniques with strong leadership and the taking of simple and clear positions. And the neologisms of Wilders help him achieve this, they are priming and framing political debate and therefore influencing the minds of the electorate. He is deliberately creating some sort of vernacular or bridge language between the politics and the people, handing the people tools, framing devices or reasoning devices in order to engage the political debate in their own way. And whether we despise or vote for Wilders, we all have to deal with the new realities he is shaping.

How to escape the frame?

Kuitenbrouwer researched the use of frames by Wilders, and ended up with four main frames he is referring to in debates or public talks, the Islamisation, Subsidies are Theft, Blueprint of the Netherlands and the Dhimmi frame. I will not go into them separately, but having only four frames displays the simplicity and clarity he is using to display the urgence of todays politics. Looking at some of the words that Wilders introduced, it is easy to see how they might have sparked political debate within a certain frame.

Next to these neologisms or new combinations, Wilders is also known for his frequent use of tropes, superlatives (“Worst government ever”) and hyperboles (“tsunami” or “disaster”) as described in the classic rhetorics of Aristotle, the art of persuasion. So next to priming, framing, fallacies are also part of Wilders’ design tools.

Neologisms of Geert Wilders20

AI Gore-papegaai

Gedachtepolitie

Haatbaard

Haatimam

Heimweeschotel

Henk en Ingrid

Hollandistan

Kopvoddentaks

Linkse hobby’s

Multicul

Overlegpaleizen

Rabat aan de Rijn

Wilders’ frames according to Kuitenbrouwer

The question rises, if Wilders is so succesful in creating or designing these new objects of reality — with questionable motives — is it not possible to repurpose these techniques in a more constructive way, if language can be perceived as being an object, is it also possible to use design-methodologies in order to construct and shape it? At least it could be useful to analyse and visualise the workings of Wilders’ designs in order to better understand and defuse them. Only then are we able to level the playing field again.

Geert Wilders does not only design his rhetorics, he also dyes his hair in a blonde color. It is assumed that he wants to hide his Indonesian roots.

Notes

- Material Cultures, Material Minds: The Impact of Things on Human Thought, Society, and Evolution. Nicole Boivin. Reviewed by Christopher S. Peebles. ↩︎

- Material Cultures, Material Minds: The Impact of Things on Human Thought, Society, and Evolution. Nicole Boivin. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008. ↩︎

- How does our language shape the way we think? Lera Boroditsky. What’s Next? Dispatches on the Future of Science. Vintage Press, 2009. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Adam's Tongue: How Humans Made Language, How Language Made Humans. Derek Bickerton. Macmillan, 2009. ↩︎

- What is an Apparatus? And Other Essays. Giorgio Agamben. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009. ↩︎

- Adam's Tongue: How Humans Made Language, How Language Made Humans. Derek Bickerton. Macmillan, 2009. ↩︎

- The Psychology of Stereotyping. David J. Schneider. Guilford Press, 2004. ↩︎

- De woorden van Wilders en hoe ze werken. J. Kuitenbrouwer. De Bezige Bij, 2010. ↩︎

- Material Cultures, Material Minds: The Impact of Things on Human Thought, Society, and Evolution. Nicole Boivin. Reviewed by Christopher S. Peebles. ↩︎

- Material Cultures, Material Minds: The Impact of Things on Human Thought, Society, and Evolution. Nicole Boivin. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008. ↩︎

- How does our language shape the way we think? Lera Boroditsky. What’s Next? Dispatches on the Future of Science. Vintage Press, 2009. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Adam's Tongue: How Humans Made Language, How Language Made Humans. Derek Bickerton. Macmillan, 2009. ↩︎

- What is an Apparatus? And Other Essays. Giorgio Agamben. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009. ↩︎

- Adam's Tongue: How Humans Made Language, How Language Made Humans. Derek Bickerton. Macmillan, 2009. ↩︎

- The Psychology of Stereotyping. David J. Schneider. Guilford Press, 2004. ↩︎

- De woorden van Wilders en hoe ze werken. J. Kuitenbrouwer. De Bezige Bij, 2010. ↩︎